Diversity. Feminism. Prejudice. Inequality. Discrimination.

These are stirring words, evoking both positive and negative emotions depending upon your personal beliefs. Maybe you’re trying hard to not to feel anything at all about them, but you can no longer deny that they represent important issues in our world today.

Perhaps any negative emotions you feel are down to personal bad experiences. Or maybe it’s because you dislike the way our society seems so focused on them right now. It’s no surprise that any discussion around these topics can get heated very quickly. But we’re not here to stoke that particular fire. Here we’ll approach these issues from a different perspective – that of a sociologist.

You see, sociology doesn’t judge. It doesn’t have a view on whether something is right or wrong. It identifies neither victims nor bad guys. Sociology just analyzes society as it is. And our CEO Marieke van de Rakt, who graduated with distinction as a Sociology major, has found that it offers a good way to start the debate on these subjects. She’ll be your guide in this article, where we’ll take a look at gender stereotypes and prejudices; Where do they come from and where are they going? Is there still a big difference between the genders? And what can we do to improve the situation?

Are you ready? Let’s begin.

The riddle of the surgeon

Read the transcriptTranscript

I want to tell you all a story.

A man and his son are in a car accident. It is a horrible, tragic accident and the father dies.

The son is left fighting for his life. An ambulance rushes the boy to hospital where they call on their best surgeon.

The surgeon rushes to the emergency room. The surgeon takes one look at the boy and exclaims: ‘I cannot operate on this young man, he is my son!’

Confused? How can this be if the boy’s father has just died? Unless…

Well, as it turns out, the surgeon isn’t the boy’s father. The surgeon is the boys mother. The surgeon is a woman.

Of course, we all know that there are female surgeons. And yet, when we think of a surgeon, the default image that pops into our heads is that of a male. This is the stereotypical image of a surgeon: a man in a white coat.

Somehow, that’s the way we have been conditioned. Let’s look at why we are programmed that way and where these prejudices and stereotypes can lead us.

So what do we mean by stereotypes and prejudice?

A stereotype is a widely held, fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing. Stereotypes aren’t inherently positive or negative, but can be frustrating for those being stereotyped. Examples of stereotypes are: the Dutch ride bicycles everywhere; Norwegians are tall, blonde and beautiful; the French love croissants.

A prejudice is a judgment (usually negative) about someone before having any information on which to form a knowledgeable opinion. Examples of prejudice are: Women are meant to be housewives; Middle-eastern people hate western culture; Gamers are antisocial geeks.

Rappers are criminals

Women love chocolate

Blondes are dumb

Teenagers only look at their phones

Girls are only interested in their looks

Vegans are annoying

What does sociology have to say about stereotypes and prejudice?

One of the first sociologists to research this in-depth was Henri Tajfel. After World War II, the accepted viewpoint was that only those with certain personality factors, such as authoritarianism, were prejudiced. But Tajfel, a holocaust survivor, disagreed. He believed that everyone is prejudiced, and he dedicated his life to finding out why we all use or have stereotypes and prejudices. His research concluded that stereotypes and prejudices serve two important functions: a cognitive function and a social identity function.

Tajfel’s experiments

Read the transcriptHenri Tajfel has an impressive list of publications. Check out his article on social identity and intergroup behavior.

Transcript

Henri Tajfel is famous for two types of experiments. The first was about information processing – what function does prejudice serve in everyday life? Tajfel proved stereotypes and prejudice help people to make the world simpler. Stereotyping is a way for us to organize information.

In order to make sense of the world around us, we put people into boxes. So, a man in a suit is a self-absorbed rich business man. A pretty girl with a phone has no depth or personality, she is just a pretty face. Tajfel showed that prejudices are a tool we use to organize and process information.

Tajfel also did another group of experiments to discover how prejudice and social identity are related. What does belonging to a group mean to us humans? Tajfel divided a group of people into two groups based on a random factor, such as a coin toss. People knew which group they belonged to, but they did not personally know anybody in their group. They were complete strangers.

Next, Tajfel chose members of the groups to give away money, both to people in their group and to those in other groups. What happened? People showed favouritism towards those belonging to their own group. Why is that?

Well, it turns out that people like to belong to a group. If you put them into a group – even one randomly assigned – they immediately begin identifying with that group. Belonging to a group makes us feel good about ourselves and gives us a sense of identity and self-esteem. We like to believe that our own group is more fun, more intelligent, or more innovative than other groups.

Tajfel therefore showed that stereotypes and prejudices are important in creating and maintaining a positive sense of identity and self-esteem. And, that we all use stereotypes and prejudice as a way to process information.

That means that everybody has prejudices: They are indeed universal.

Origin of prejudices

So now we’ve established that everyone has prejudices, it’s time to explore where they come from.

Let’s be clear: the subject of gender is not black and white. People identify differently on the male-female continuum. However, within the scope of this article, for simplicity, gender will be considered binary.

In most western societies, people tend to consider men and women as equal. We don’t need to convince anybody that women should be able to, for example, vote, have an education, or pursue a scientific career. Most people agree that women should have exactly the same rights and opportunities as men.

Does this mean that the feminist revolution is really over? Are men and women really equal? Unfortunately, that’s not the case at all. Just look at the number of people working in the tech industry. There are fewer women in leading positions and there are fewer women in technical roles – like developers for example. If we look at the salaries of men and women, we also see big differences. Men, on average, make more money than women. So, although men and women are perceived as equal, they are not (yet) treated entirely equally. So why do these differences exist? Much of this is down to prejudice.

Many of the differences between men and women are not biological at all, but rather sociological. I will go into the sociological part, the nurture part, shortly, but let’s start with nature.

Biological prejudice (nature)

It’s of course true that there are some differences in men and women of a biological origin. Women are able to bear children, for example, whereas men aren’t. But these biological differences have become gender role stereotypes in and of themselves. Such as how we tend to think that men are stronger than women, simply because they are generally more muscular. But there are plenty of exceptions to this rule, so assuming a woman isn’t physically strong just because she is female, is definitely a prejudice.

But which differences are the result of biology? There are no easy answers to this. So join us for a little game of fact or prejudice.

No… men and women are equally smart. The average IQ for both men and women is 100. However, the distribution of IQ across the scale is different for men and women. At least, that is what some scientists claim. Because, while there is scientific consensus about the average IQ, there is still some debate over the distribution. Many scientists say that while average IQ is similar between the genders, the IQ distribution curve for men is a bit flatter than that for women. So more men are in both the really high IQ range and in the really low IQ range, and more women sit in the middle of the graph (with an IQ of around 100). Scientists are debating this matter and will be for some time.

Yes, men are generally taller than women. All over the world men are – on average – taller than women, the difference being around 10cms. That said, I am a woman and I’m 184cm tall, which means I am usually taller than most of the men in the room. So, while there are differences between groups, there are also major differences within those groups.

This is a tricky one. Yes, men are better at maths than women, on average, in most countries. But there are also many countries where men and women score equally in maths tests. And, there are some countries where women score better than men.So, men are in fact better than women at maths, but this is clearly not biological. Because women score better in some countries, it cannot be genetic. So, the explanation for the differences in maths scores has to be sociological.

No, the brains of men and women are not entirely different. It is not possible to see just from looking at a brain whether it belongs to a man or a woman. In essence, the male and female brains are pretty much the same. There are some minor differences though. On average, men’s brains tend to be slightly larger and women’s brains have a thicker cortex. Overall though, the male and female brains function in the exact same way. Of course, scientists are debating this one as well.

So, as we’ve seen, the brains of men and women are essentially the same. Men do tend to be better in maths, but this cannot have a biological cause. Similarly, there is no biological explanation as to why so few women end up in leadership positions. And neither is there a biological explanation as to why there are so few women in tech jobs. So, the explanation for why there is a lack of women in the tech industry must lie with nurture.

Societal prejudice (nurture)

Studies have shown that prejudices emerge in early childhood. The way we raise our children and the stories we tell them have a big impact on the types of stereotypes and prejudice they’ll hold in life.

From the moment our children are born – and nowadays even before then – they are treated differently according to their gender. We dress girls differently from boys. We give them different toys to play with. We even talk to them in a different manner.

Now, that is not necessarily a bad thing. You don’t have to feel like you’re a bad parent because of that.

I have three sons and one daughter. I love having a girl. I dress her differently. I myself love being a girl. I love pink. I love to wear dresses. It’s no bad thing to be a girly girl. It’s no bad thing to have a daughter who enjoys wearing dresses and playing with barbie dolls. It is, however, important – and I will go into that a bit more later on – to be aware of the fact that girls are treated differently. It’s important to keep thinking about how this will affect her and my three sons.

Marieke

But nurture is about more than just parenting. Gender stereotyping also happens in schools. A study from 1994 showed that teachers treat girls differently from boys in the classroom. While boys are praised when they show correct knowledge, girls are praised for good or compliant behavior. Girls are criticized for getting things wrong, while boys are criticized for misbehaving.

I recently attended a play at my kids’ school. It was medieval themed. First, the girls did a dance. They were all dressed like medieval princesses. After that, the boys came on stage carrying swords and did a sword-fight demonstration. I asked the teacher afterwards why she chose to separate boys and girls. She reacted defensively. ‘If your son or one of the other boys had wanted to play a princess, then of course that would have been allowed.’ And she really meant that. But that means that children of the age of 6 have to go to the teacher and ask for another role. Most children will not do that. Which means everyone was watching a show in which all of the girls were being pretty, and all the boys were acting tough. The parents, teachers, and the children were (once again) reinforcing their gender stereotypes.

Marieke

Gender stereotypes are also common in advertising. There is a Dutch brand that sells shampoo ‘for strong and smart boys’, and a shower gel ‘for sweet and beautiful girls’. Marieke’s daughter was confused. “I want to be smart,” she said, “but I do not want to be a boy.”

Advertising aimed at children starts from these stereotypes. Water guns for boys, Barbie dolls for girls. And so it continues into adulthood: Cars are for men, kitchen appliances are for women. All these things combined lead to strong and potentially harmful gender stereotyping.

So if we buy into this, what stereotypes do we end up with?

Female stereotypes

Women are sweet, kind, and nurturing. Women are beautiful, modest, and gentle. Women are emotional, a little irrational, and cheerful.

Male stereotypes

Men are competitive, smart, and independent. Men are strong, they are leaders. Men are analytical and decisive. Mysterious, tough, but loving.

What happens when people do not fit these stereotypes?

You may be thinking: ‘These gender stereotypes are all positive things, so what’s the big deal?’ But have you considered what happens if people do not fit into common stereotypes? To answer that question, let’s look at a case study.

A group of people was divided into two groups of 30 each. The first group of people got to read this case: ‘Heidi Roizen became a successful venture capitalist by using her outgoing personality… and vast personal and professional network that included many of the most powerful business leaders in the technology sector.‘

The other group of people got to read the exact same case, only the name wasn’t Heidi, it was Howard. Afterwards people were asked: ‘Do you think this person is qualified? Do you think this person is smart? Do you like this person.’

There were no differences in the opinion of Heidi and Howard concerning their qualifications. People thought that both Howard and Heidi were equally smart. However, while people liked Howard, they did not like Heidi. People wanted to be friends with Howard but not with Heidi.

People tend to dislike those who are different from their gender stereotypes. We think it’s weird, it doesn’t add up, it’s not inline with what we consider ‘normal’.

This means that women who take charge, who hold leadership positions, are often perceived as bitches. Women who pursue a career in computer science are perceived as geek girls. Men who are caring and nurturing are perceived as weak. And sensitive men? Well, obviously they are not real men.

It makes us feel uncomfortable if people act differently from how we expect them to act. If we don’t understand it, we tend to dislike it.

Consequences of stereotypes

So, what does this mean for differences between men and women? What exactly are the consequences of prejudices?

Speaking from my own experience: I don’t want to be a bitch. I really want people to like me. I was afraid to step up and take a leading position for such a long time. I was genuinely afraid that people would not like me anymore. I was really struggling to ‘be myself’ and take charge and be a manager. And I think this is the case for many other women too. They have to step outside of their gender role where they are expected to be modest, kind and caring, and into a role where they need to lead, be decisive and a little bit bold. That’s hard.

Marieke

This means that women have a pretty hard time finding their way into traditionally male-dominated occupations (such as tech) and leadership positions, but at the same time, men have a hard time if they want to work in, for example, childcare.

Men are even fighting their gender role if they want to look after their own children. Men are often overlooked or neglected in this way, because they are not expected to be caring and nurturing.

Open source development

Read the transcriptTranscript

Let’s take a look at a study on an open source development project. This study analyzed 3 million pull requests. A pull request is when a developer makes changes to the code of a software project, and then asks permission to officially include these changes in the project. The project leads then decide whether to accept or deny this request.

This study focuses on the pull request success rates of each gender. At first glance, the results look quite promising:

The overall success rate for women was 78.7% and for men it was 74.6%. So, that doesn’t look like gender inequality at all.

However, if you drill down into the results, you find that these results include insiders to the project – people who knew each other, and each other’s work.

It turns out that the results are quite different for people who were unknown to the project leads.

For non-insiders – new ones – the acceptance rate for women was much lower at only 58 %. For new men it was 61%. And then there were a lot of people who had a gender-neutral name and user profile, meaning the project leads did not know their gender. Among these people the acceptance rate is a bit higher. Men with a gender-neutral profile had an acceptance rate of 65% and for women it was 70%. And this is interesting.

The results show that women had a good chance of getting their pull request accepted if they were known. Higher than men even. But if they were unknown, the gender stereotypes seemed to kick in. Will a woman’s development skills be as good as a man’s?

For a woman who is new, you’d have the best chance of getting your pull-request through if you concealed your gender. Chances are that people will assume you are male, just because, stereotypically, the majority of developers are male.

This study shows us that our prejudice kicks in when we don’t know people. This is when we need that mechanism to make sense of the world. It’s the only information we have to work with.

It turns out that in uncertain situations, people are most prone to use prejudices. And that’s something we all should be more aware of. Uncertainty can lead to prejudice.

Want to read the entire study? Check it out!

Women still have a tough time taking the lead. Look at the Fortune 500 and you’ll see that, of the 500 biggest companies, only 24 are led by women. If we look at the WordPress ecosystem, the picture isn’t any better. Of the 20 most influential WordPress businesses and companies today (according to WPbeginner.com) only 2 are led by women.

of the Fortune 500 companies are led by a woman

of the most influential WordPress companies are led by a woman

So what can we do

We cannot change society. Many of the inequalities existing today come from our culture. It is in our schooling, the media – everywhere. We can’t really control that.

Marieke, for one, tries to change things on a micro-level. “I talk to the schools my children attend and try to make them aware of their gender stereotyping. And, the marketing of the shampoo products for boys and girls was in fact changed after I – and a lot of other people – tweeted about it.” So little things can make a difference.

Be aware

The first thing we can do is to be aware of our prejudices. Be conscious of stereotypes and be aware of what our role is. Marieke is always aware that she is not raising her daughter in exactly the same way as her sons.

Another example: Men are thought of as being more decisive, more natural leaders, more confident, and so men are much more likely to ask questions at conferences. That doesn’t mean that women don’t have anything to contribute. They are just socialized in such a way that it isn’t as easy or natural for them to speak up. They are socialized in a way that’s taught them to be more modest.

If people are aware of a woman’s tendency towards modesty because of cultural conditioning, we can break through. We can help women to stand up and ask questions, for example by asking them to do so beforehand. Their example might lead other women to follow their lead and ask more questions.

Looking at another example: Job interviews. If we are aware that women are generally more modest, then maybe all it takes to look beyond your prejudices is a little extra thought. Perhaps we need to ask different questions in interviews to get the answers we need.

At Yoast, we like to try that bit harder with recruitment, because that allows us to truly hire the most competent employees. That’s why Marieke started the Women Empowerment Project. She wants to help women be more confident and stand up for themselves a bit more. And at the same time, Marieke wants to research whether or not we ourselves hold a gender bias that is preventing women from growing within our company. Yoast has some really bold and passionate men at the top of the organization. And we actively encourage more women, but there could still be prejudices and old habits lurking. Yoast is looking into this and trying to do better, and we believe more companies could benefit from this approach.

Strong female role models

Another thing we lack is strong role models. The more people we see in roles that challenge their gender stereotypes, the more we will get used to it. This is why Yoast strongly believes in diversity on the stage (at WordCamps, for example). If the lineup at conferences and events is diverse, everyone will hopefully recognize something of themselves in the people they see in the spotlight.

That’s why we started the Yoast Diversity Fund for traditionally underrepresented groups. We cover expenses and travel costs for those who otherwise couldn’t afford to speak at WordCamps or similar conferences. Having these people on stage is fighting stereotypes. That’s crucial.

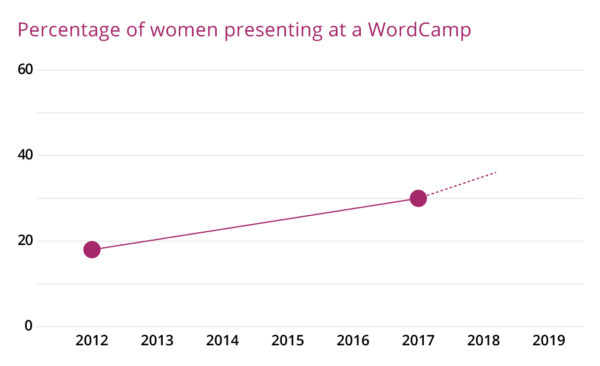

WordPress has become a community that excels at this. They deserve a round of applause! There are not many statistics available, but what we have found is inspiring:

In 2012 women gave 19% of talks at WordCamps. In 2017 this percentage had increased to 30%. So in only 5 years, WordPress has managed to get 11% more female speakers on stage. That is amazing.

Conclusion

If there is one thing to take away from this story, let it be this:

Everybody holds prejudice. It’s totally normal. But it’s how we handle these prejudices that makes the difference. If we want to live in a world of mutual respect, where everyone is free to be who they want and do what they want, this is where to start.

If you want to learn more, you can find a list of additional reading/viewing materials below. They all inspired and informed the things we’ve talked about here.

Or, if you want, you can share this article with others. Even small actions like that, learning something new or starting a conversation, can move us closer to a kinder, more tolerant world.

TedTalks to watch:

- Sheryl Sandberg – Why we have too few women leaders

- Anne-Marie Slaughter – Can we all “have it all”?

- Maureen Fitzgerald – Implicit bias – how we hold women back

- Paul Zak – The differences between men and women

- Daphna Zoel – Are brains male or female?

- Janet Crawford – The surprising neuroscience of gender inequality

Books to read:

- Inferior: The true power of women and the science that shows it by Angela Saini

- Lean in by Sheryl Sandberg

- The moment of lift – Melinda Gates

- That’s what she said: what men need to know (and women need to tell them) about working together- Joanne Lipman

The post Diversity, inequality, and prejudice; a sociological exploration appeared first on Yoast.

from Yoast • SEO for everyone https://ift.tt/2llEytU

No comments:

Post a Comment